Hosting an International Belly Dance Artist in the U.S.: Can You Actually Make Money?

Want the budget spreadsheet + full event planning workbook?

Drop your email below and I’ll send you the exact tools I use to plan profitable workshops (checklists, timelines, pricing, the whole thing).

Hosting an international belly dance artist sounds glamorous.

It sounds like prestige. Like leadership. Like you’ve “made it.” Like you’re building culture in your city.

And sometimes it is.

But sometimes it’s also you, at 2:00am, staring at your registration numbers and realizing you might have accidentally paid $4,000 for the privilege of being stressed and resented by everyone you know.

Because here’s the truth:

Hosting international artists can absolutely be profitable.

But it can also be one of the fastest ways dancers lose money, burn out, and convince themselves that “this industry is impossible.”

So let’s talk about it.

Not like dancers who hope for the best.

Like business owners.

The Question Everyone Asks (And the One They Should Be Asking Instead)

The question I see is always:

“Is it even possible to host an international artist and make money?”

And the honest answer is:

Yes.

But not automatically.

Not because the artist is famous.

Not because you’re passionate.

Not because your community “should” support the arts.

Profitability is not a moral reward for devotion.

It’s a math problem.

And a demand problem.

And a reputation problem.

So the better question is:

Can you sell enough seats in your market, with your current reach, to cover costs and generate profit?

Because that’s what hosting is.

It’s not just “bringing an artist you love.”

It’s you taking on risk.

Hosting events is also a decent way to get yourself hosted, but that’s a different discussion for another blog post.

Step 1: Visa Reality (And Other Legal Things We Pretend Not to Think About)

Before we even talk about profit, we need to talk about legality.

Because dancers love to act like this is a mysterious grey area when it’s actually very straightforward.

Any non-American teaching or performing in the United States on a tourist visa is illegal. It doesn’t matter if they have an Egyptian or Canadian or British passport. It’s not legal without the proper paperwork or on a tourist visa. Full stop. End of story.

That has always been true.

That is still true.

That will continue to be true.

Does it happen? Yes.

Has it happened for decades? Also yes.

Is the risk level high and the consequences…more consequential than ever right now? Absolutely.

If you are hosting, you need clarity on:

what paperwork exists (or doesn’t)

whether the artist understands their situation

and what your own risk tolerance is

Because hosting isn’t just “bringing someone in for the love of the art.”

You’re attaching your name to:

the advertising

the venue

the payments

and the logistics

You are the visible organizer.

So don’t pretend this is just vibes and veils.

Other Legalities

Beyond immigration, there’s another layer dancers tend to ignore:

You are collecting thousands of dollars.

Which means you are running a business event.

Even if it’s “just a weekend.”

If you’re bringing in thousands in registration fees, you should be thinking about:

Do I have an LLC or some kind of business entity set up?

Am I using a proper contract?

What happens if someone gets injured at the venue?

How am I reporting this income?

What tax obligations do I have?

Here’s the part people conveniently forget:

When an artist quotes you $1,500, that is their net.

They are not factoring in:

your processing fees

your local taxes

your state sales tax (if applicable)

or what happens when thousands of dollars hit your bank account

They get paid.

You deal with the rest.

And if you’re collecting money and paying it out “under the table,” you are operating in a grey area- and the larger the event, the less cute that grey area becomes.

The IRS does not care that it was for culture.

They do not accept hip drops as payment.

I’m not going to get into full accounting mechanics here, but if you’re serious about hosting, you should speak to an accountant, and possibly a lawyer about:

income reporting

contractor payments

whether you need to issue 1099s

sales tax (depending on your state)

and how to structure this properly

Because if you’re going to take on the risk and the workload of hosting, you might as well do it properly.

Professional doesn’t mean corporate.

It means you understand that once money changes hands, this is no longer just art.

It’s business.

Step 2: The Artist Fee & other expenses

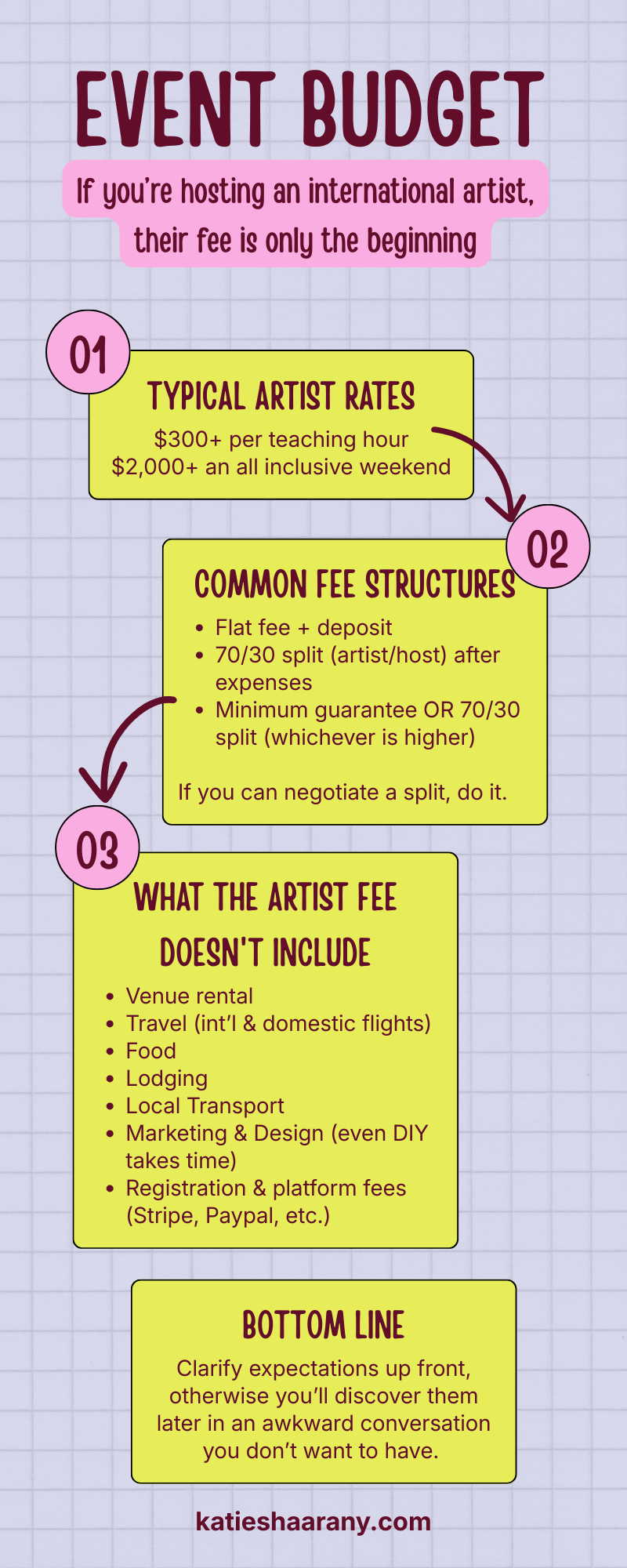

Many reknowned artists will charge upwards of $300 per teaching hour or $2,000+ for an all inclusive weekend.

Sometimes you can arrange a split (generally 70/30 in the artists favor after expenses) and I highly recommend pushing for this as the organizer.

If it makes the artist more comfortable, you can frame this as <minimum fee OR 70/30 split, whichever is higher> to ensure that you are both invested into making the event mutually beneficial.

The artist fee is only one part of the cost.

Here’s what else is almost always involved:

Venue rental

Even if you “know a studio,” it’s usually not free.

And if it is free, you are still paying in favors, relationships, or future expectations.

Travel

International airfare is not cute right now.

And domestic flights are not exactly cheap either.

Lodging

Sometimes artists are willing to stay with someone.

But “stay with someone” still needs to be safe, clean, and reasonable.

If you’re hosting someone in a chaotic home with no privacy and a cat that bites, you are not saving money.

You are creating a future rumors and drama.

Local transportation

Airport pickup. Rides to the venue. Food. Possibly a rental car. Possibly Uber fees. Possibly gas reimbursement.

Marketing and design

Even if you do it yourself, you’re spending time.

And time is a cost.

Registration platform fees

PayPal fees. Stripe fees. Website fees. Ticketing platform fees.

Artist expectations

Some artists charge separately for:

performances

judging competitions

private lessons

VIP intensives

meet-and-greets

photo sessions

Sometimes it’s all bundled. Sometimes it isn’t.

And if you don’t clarify that upfront, you will find out later.

Usually in the form of an awkward conversation you didn’t want to have.

So, what does a weekend actually cost?

If you add all of this up, a weekend like this often lands around:

$3,000–$4,000 total cost minimum

I’m not saying this to scare you.

I’m saying it because dancers consistently underestimate costs and then act shocked when the event doesn’t profit.

You can’t be surprised by math.

Step 3: Break-Even Math

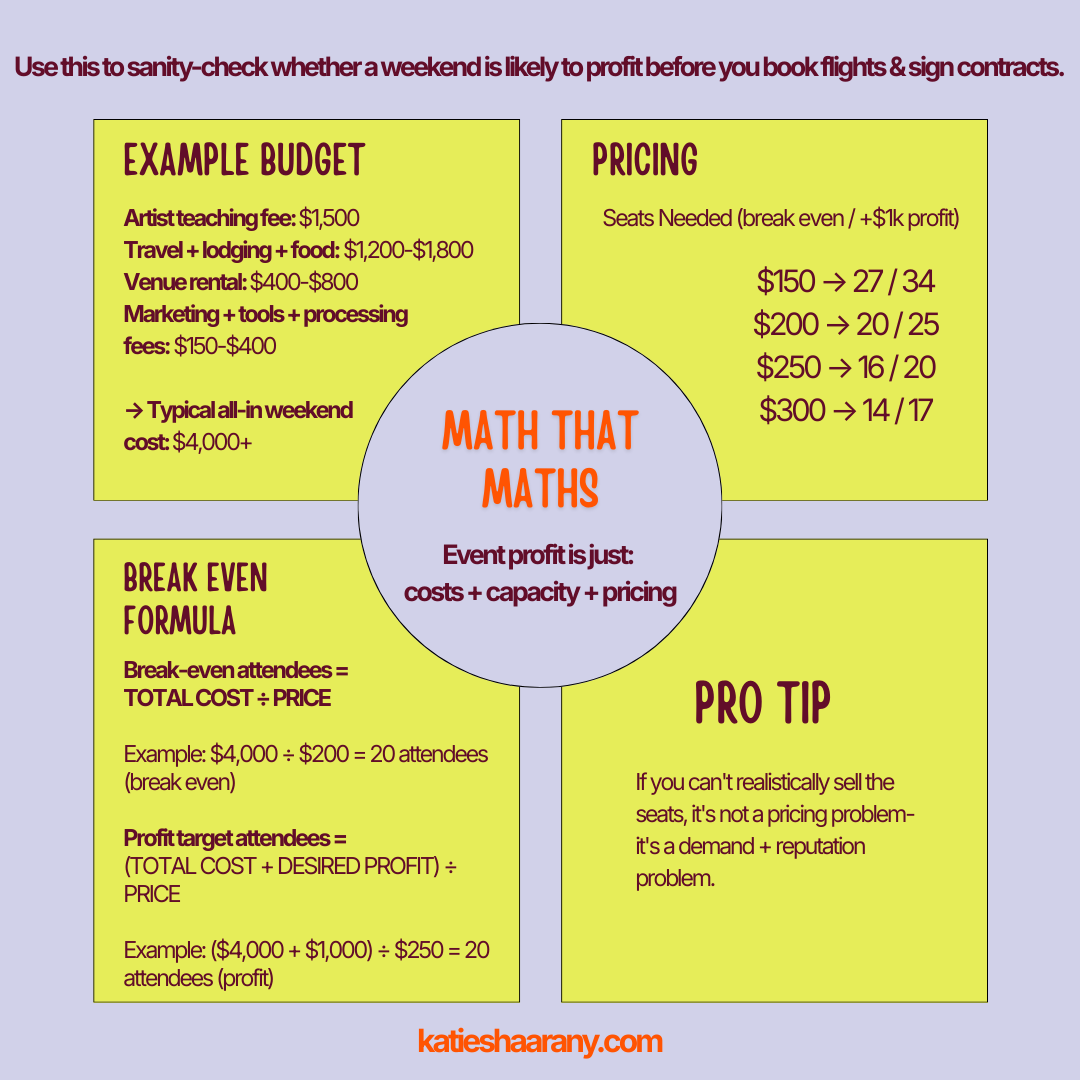

Let’s assume your total cost is $4,000.

Now you need to decide your pricing.

If you charge:

$200 for the weekend (4 hours of workshops)

You need:

20 people

just to break even.

Not to profit.

Not to pay yourself.

Not to compensate for the 40 hours of work you’ll do organizing it.

Just to not lose money.

Let’s say you want to make $1,000 profit (thereby paying yourself $25/hour to organize…which I’ll leave up to you whether that’s worth it or not.)

That means your target revenue is:

$5,000 total revenue

So you might need:

25 people at $200

or 20 people at $250

or 17 people at $300

And this is where dancers start to panic because they realize:

“Oh… this is not about the artist fee.”

This is about whether you can sell seats.

Step 4: The Real Question — Can You Sell 20–30 Seats?

This is the most important question in the entire conversation.

Because most dancers assume that if the artist is “good enough,” people will show up.

That’s not how humans work.

Humans don’t go to an event because it is objectively valuable.

Humans attend events like these because:

they trust the host

they understand the benefit

they feel excited

they feel socially safe attending

and they believe it’s worth their money

So you need to ask yourself:

Do you actually have the community for this?

Do you have:

a consistent student base

a community that is used to paying for workshops

people who have disposable income

dancers who travel

dancers who invest in training

a regional network beyond your immediate circle

Because if you don’t, your marketing plan becomes:

“I hope strangers on Facebook feel like driving 4 hours and spending $250.”

And hope is not a strategy.

This is where most hosts break down

Most dancers want to host.

But they don’t want to do the work required to sell.

They don’t want to:

post consistently

email consistently

message studios

coordinate partnerships

reach out to teachers

ask for support

set deadlines and follow up

build hype without sounding desperate

They want to make one announcement and then have the community do the rest.

And when that doesn’t happen, the story becomes:

“People don’t support the arts.”

No.

People don’t support unclear offers from hosts they don’t trust enough yet.

Ad break. Yes, this is about you.

If this breakdown feels slightly exposing, that’s because I don’t sugarcoat business.

Inside Bellydancers in Business, we take this same “math over vibes” thinking and apply it to everything you’re building.

Hosting.

Pricing.

Offers.

Visibility.

All of it.

It’s eight months. It’s the final cohort. It closes April 3.

If you want long-term access to this level of thinking instead of just reading my blog and nodding, go look at it.

Step 5: You’re Not Just Selling the Artist — You’re Selling Your Reputation

This is the part dancers don’t understand until it hurts.

When you host an event, you are not just selling the artist.

You are selling:

your taste

your leadership

your follow-through

your professionalism

your ability to create a good experience

Because in the eyes of your community, the artist is a risk.

They don’t know:

if the workshops will be worth it

if the venue will be comfortable

if the event will be organized

if it will be awkward

if it will be cliquey

if it will feel safe

if it will feel worth the money

So they use the only metric they have:

you.

If they trust you, they’ll register even if they’ve never heard of the artist.

If they don’t trust you, they won’t register even if the artist is amazing.

That’s why your brand matters.

Not your logo.

Your reputation.

Your track record.

Some dancers can fill rooms. Some can’t.

Some dancers can sell 30 seats easily.

Not because they’re better dancers.

Because they’ve built years of trust and visibility.

They’ve been active. They’ve been consistent. People know their name. People have had good experiences with them.

Other dancers struggle to sell 10 seats.

Not because they’re untalented.

Because they haven’t built the relationships yet.

This is dancer-by-dancer.

And if you don’t want to acknowledge that, hosting becomes a very expensive ego project.

Step 6: Demand and Community Alignment (One Real Reason Events Fail)

This is where I see hosts make a huge mistake.

They choose an artist because they personally love them.

Which is valid.

But your personal obsession is not a marketing plan.

You need to ask:

Does my community know this artist?

Do they care about this artist?

Do they understand why this artist is worth paying for?

Does this artist’s style match what my students are interested in?

Is my community at the right technical level to benefit? (I have HILARIOUS stories about this one…DM me, lol.)

Do I have the influence to educate demand before the event?

Because sometimes the artist is phenomenal…

…but your community is not ready.

And if your community is not ready, it doesn’t matter how brilliant the artist is.

You will not sell the seats.

“But the art is important!”

Yes. The art is important.

But you are not running a nonprofit museum.

If you are hosting, you are running a business event.

That means you need to understand the difference between:

“This is high quality”

and

“This is what my market will buy right now.”

That gap is where dancers lose money.

Step 7: Notoriety Matters (And Yes, It’s Annoying)

People don’t just pay for skill.

They pay for perceived value.

Notoriety helps because it reduces the risk in the buyer’s mind.

People are more likely to register if the artist is:

well-known

respected

talked about

seen as prestigious

already desired

This does not mean Instagram famous.

But it does mean that demand exists.

If demand doesn’t exist, then you (the host) need to create it through your own influence and marketing.

And most dancers underestimate how hard that is.

They assume the artist’s name will do the work.

Sometimes it will.

Often it won’t.

Step 8: Workshops Alone Rarely Create Real Profit

This is the other truth dancers don’t want to admit.

Workshops alone can break even.

Sometimes they can profit.

But usually, the workshops are not the profit engine.

The real money makers are:

gala shows and open stages

competitions

VIP packages

vendor fees

private lessons

add-on experiences

photography packages

Whether you like it or not, these are often the pieces that move an event from:

“We covered costs.”

to

“We actually made money.”

If you are only hosting two workshops and hoping the weekend is profitable, you’re playing on hard mode.

Successful hosts treat the weekend as an ecosystem:

workshops anchor attendance

shows/competitions drive revenue and excitement

add-ons create margin

That’s not glamorous.

It works.

Step 9: The Biggest Mistake Hosts Make

The biggest mistake is not pricing.

It’s assumptions.

Hosts assume:

“People will come because the artist is famous.”

“My community will support this.”

“I’ll post a few times and it’ll fill.”

“Everyone will share it.”

This is not strategy.

This is wishful thinking.

And the reason it’s so common is because dancers were never taught marketing as a skill.

They were taught to dance and hope.

Lastly: Why I’m Direct and Kind of A Bitch About This

Because I’ve done it.

I wasn’t an A-list competition dancer.

I wasn’t in a major city.

I didn’t have the “right” credentials on paper.

And yet I sold out shows.

I sold out classes.

I hosted events and made money.

Not because I was the best dancer in the room.

Because I intuitively understood audience, positioning, and trust.

And I’ve helped my clients do the same.

My clients aren’t necessarily ~fAmOuS~ scene names.

They built their own table.

They:

host international artists

fill workshops

raise prices confidently

increase revenue without over-teaching

build sustainable businesses rooted in their art

That doesn’t happen by accident.

It happens because they stop guessing and start building.

So… Can Hosting Be Profitable?

Yes.

But only when:

the math is clear

the audience is aligned

demand exists (or can realistically be built)

the host has credibility and follow-through

and the event is structured like a business, not a vibe

Hosting isn’t magic.

It’s math, reputation, and execution.

If You Want to Do This Without Guessing

This breakdown is exactly why I’m running my final belly dance business mastermind.

Because dancers don’t need more bullshit advice from mentors that are just reliving their glory days or colleagues whose business strategy boils down to “be hot on Instagram”.

You need:

structure

clarity

strategy

and the ability to build demand over time